She was born in the throes of a fierce Kansas thunderstorm on a hot summer night. The wind hurled the rain against the hospital windows until I thought surely they would break. The lightning splintered the night sky and the thunder cracked open the heavens and the splintering and cracking open of my body seemed to answer back with an ever increasing intensity. Paul sang to me, he read to me, he talked to me and he prayed over me and the storm raged both inside and out. I was exhausted and I was stuck and it seemed we were at an impasse. I had been in this room all day, all evening and all night. The dawn would break before long. The doctor explained “You are stuck at eight centimeters and have been there for too long. We are going to take you to delivery and see if you can push the baby out. If not, we’ll bring you back.” What he meant was, “If you can’t deliver the baby, we will bring you back to surgery and do a Caesarian” (today that decision would have been made hours earlier). What I heard was, “. . . we will bring you back to this room of torture and you will continue to do what you have been doing for the last bazillion hours.” And I knew that hell would freeze over before I would let that happen.

I no longer remember how long I pushed, but I knew that I was nearing my limit. Later, when I looked at myself in the mirror, I realized that I had broken what looked like every capillary in my face from the sheer force of the pushing. The doctor tried forceps and I shrieked at him to get away from me. He sat down on a stool a little ways away to rest (what did HE have to rest from?!) and I knew any minute he was going to call this. And then it was over. In one long and horrific contraction. All at once – just like that. No head and then shoulders and then body. It was like a cannon ball being shot out of the cannon. The doctor jumped, ran, grabbed (several times) and I heard him yell, “I GOT IT!” Her whole body came flying like a bat out of hell, face up, eyes wide open and he caught her by one foot . It was a hard-won fight, but she had prevailed and she would be a fighter for the rest of her life.

We took her home from the hospital to the upstairs apartment of an old, un-airconditioned house (this house and the Kansas summer heat are detailed in other stories). We had acquired a working window air conditioner and so we could cool one room, the living room. On really hot nights we would put the older two kids and Paul on the floor, and I would sleep on the couch. By the time we got home from the hospital the worst of the heat had broken and so the kids were back in their room and Paul and I and the baby slept in the living room: Paul on the floor, me on the couch and the baby in the cradle. Our first night home Paul insisted, “After what you’ve been through, you need to rest (no argument from me there) so when she wakes up, I’ll get up and bring her to you and you just stay put.” We had a plan. About 2:00 a.m. I heard her stirring. “Paul, she’s awake.” Nothing. She starts to whimper. “Paul, can you get her?” Nothing. She begins to cry. “PAUL, can you bring the baby to me?” Nothing. “Okay. I’ll just get her myself.” Nothing. By now she is screaming as am I, “PAUL!!! WAKE UP!!!!!!” At which point, he sat up, put his pillow carefully in my arms, and passed out cold. But his intentions were good.

Maybe it was because it had taken all of her energy just to be born, but from the first day, she slept. . . a lot. Within a couple of days, she was sleeping for 8-10 hours at night, with long stretches in the daytime as well. It was nothing like the first two but I figured each one is different and all was well. . . until we took her to the doctor for her follow up. The doctor weighed her and the drop in her birth weight was alarming. “How often is she nursing?” the doctor demanded. I explained that sometimes during the day she would go for 6 hours and at night 8-10. “But she can’t be hungry,” I assured her pediatrician. “She doesn’t cry.” “Mrs. Abbott, your baby is starving. She’s too weak to cry.” But I cried. And then we went home and set a timer and woke her up every two hours around the clock and every day we took her to the doctor’s office to weigh her in and slowly she began to gain weight and to thrive although it took her an entire year to double her birthweight to 16 pounds. I have always thought that maybe she took that first year to recover from the night we battled through the storm and to prepare herself for the battles she would fight throughout her life.

To quote the bard: “And though she be but little, she is fierce. ” She was not much past her first birthday the night we put her to bed in her crib and retired to the living room to unwind from the day. After about an hour she appeared in the doorway. Really??! Already she was climbing out of the crib? I knew she was a climber but I hadn’t been prepared for this – not yet. But I really was not prepared for what I found when I returned her to bed. She had dismantled the crib, pulling the bars out one by one until she had a created an escape hatch big enough for three of her to wiggle through. But that’s not all. She had removed the sheet from the mattress and discovered a tiny pin-prick of a hole. And now, covering the bedroom floor, were layers of cotton stuffing which she had systematically removed from said mattress until she had almost entirely emptied it of its content.

It was Thanksgiving Day and she was three. She was supposed to be napping. I think it started with the chair. Or maybe it was the piggy bank. Wherever it started, it ended with a trip to the emergency room. She had climbed onto the rocking chair to reach the piggy bank on the shelf and when they all came tumbling down, the piggy bank was shattered and the gash in her chin was going to need stitches. They put her little three year old body on the table wrapped in a papoose sort of straight jacket to keep her from moving because, the doctor explained, nobody could get out of that. She would have none of it and to their astonishment (though not to mine) she was quickly free and fighting them off. The doctor told Paul, “You’re going to have to help the nurse hold her down because we can’t do this if she’s moving and there is no way she will be still without restraint. Her dad leaned in. “Fathie, if you are perfectly still and do not make a move and let them put the stitches in your chin, I will take you for ice cream when we are done.” Okay – she whispered back and her body lay perfectly still and unflinching. Finding someplace to get ice cream on Thanksgiving Day proved to be problematic. But a promise was a promise and after driving the town, we stopped at 7-11 and bought a half gallon of ice cream.

Maybe she was always trying to recover that feeling of flying through the air that she had at the moment of her birth and the sense of being freed from the confines of the womb. She loved the freedom of gymnastics – flying through the air as she came off the vault or doing dismounts off the balance beam. She climbed to the top of the tree in the backyard and when her braids got tangled around the branches, she sent her sister to get me. “Sorry, I don’t do heights. You’ll have to wait till Dad gets home.” So she happily passed the time from her perch overlooking the world until assistance arrived. She loved the biggest and baddest rollercoasters at the theme parks. It was in the days before height restrictions on rides and she begged Paul to take her on a particularly daunting one at Busch Gardens. He hesitated, I think partly because HE wasn’t too keen on it. But she would not be deterred, and so he stood in the line with her and did his best to talk her out of it. As they were being buckled into the car he said again, “It’s not too late. Are you sure you wouldn’t rather ride something else.” She would not. And as they plunged to what felt to be sure and sudden death, he looked over at her. She set her jaw and hung on for the ride and loved every minute of it.

She was and is an obsessive organizer. She clipped coupons every week from the Sunday paper and during our monthly grocery shopping trips was quick to assure me that we could afford to buy the more expensive cereal or snack because she had a coupon. She loved to organize the pantry alphabetically and fussed at me when I did not return items to their proper place. “It would help,” I told her, “if your spelling were better.” Why would I think to put jello under “g”?” She couldn’t have been older than eight when a friend of mine with several small children of her own hired her to be her house cleaner. She would go once a week to Libby’s house: organize the kids’ toys, clean under their beds, rearrange the closets, and heaven only knows what else. When she was still a toddler her grandmother called her “the bag lady” because she always had a bag to carry all of her stuff and her accessories. Periodically she would stop mid-step, dump the bag out on the floor and take inventory and if even so much as a doll’s sock was missing, a massive hunt would ensue until said item had been located. My mother marveled that she could keep track of what was supposed to be in the bag at any given time; perhaps this was the beginning of her obsession with list making that would last a lifetime.

The organizational gene she got from her father. Along with his crystal blue eyes and his wanderlust and love for road trips. They are both wordsmiths and introverts and voracious readers. From me she carried the recessive gene that gave us the only red-headed grandchild though she herself was the only one of the six to have dark chestnut hair instead of red. She got the cancer gene that struck both my sisters and would not once but twice rear its ugly head in her body before she reached the age of 40. She got from me her love of summer heat and baking pies. And if she inherited her love of the open road from father, from me she got the “which way is north?” gene. I think she may be the only person who was as excited as I was when the GPS became standard operating procedure.

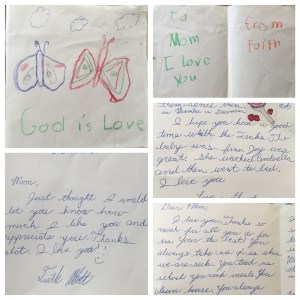

From the time she learned to make letters, she was a writer and It was not at all unusual to find on my bed at the end of the day a card or note she had written and left there for me to find.

In the months she lived in Germany she wrote often and eloquently of all she was learning about the land, the culture, the people and the history. When she went away to college, she wrote long and frequent letters home – sharing her life with us as it unfolded. And then again when she moved to Chicago and started her family, her pages-long, hand-written accounts of her life and her thoughts and her musings found their way often to our mailbox. I treasured them all.

As I look back over them now, these boxes filled with her letters, it reminds me how much we have lost with the advances in technology. Her message has changed since those childhood, college and young adult days. Her voice has always been her own.

When the storm was over and the wide-eyed baby girl was in my arms, I knew the name we had chosen was the right one. Faith Leanne – born August 12, 1976. “Faith, without works, is dead, ” writes James. It had taken a tremendous amount of hard work, on both her part and mine, to make it happen. But she was here in this world with all of her beauty and her giftedness and her struggles. She was a survivor and a message to us of God’s grace and of the faith it takes to endure the really hard times. As an adult she would choose a different name for herself, and I’m okay with that. Because, in the end, we all choose our own identities and our own stories, though they are forever and inextricably linked with those we call family.

Post Script: Let me just say how intimidating it is to write about a writer. She would say it so much better and with such poetry, but I can only tell it from my perspective and with my voice – so it is what is : a story about thunder and lightning and love.