When I was little I thought my sister Minnie was a queen. She was beautiful and tall and regal and comported herself with the air of someone who should rule over a kingdom – not a farm or a feedlot. By the time I knew her, she wore her strawberry blonde hair in a french twist and dressed with the style and class of someone born to royalty. Nothing made me happier than when someone in the family would say, “You look like your sister Minnie.” But of course, I didn’t. I was short, had an unruly mass of dark auburn hair, and was lucky if my socks matched on any given day. But still . . . it was something to which I aspired.

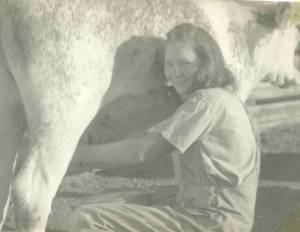

This queen-like woman who dressed and carried herself with such class was a child of the Great Depression. Born in 1931, she was the fourth of the five children my parents were struggling to feed and clothe with no job and no money. When I was in grade school I mentioned to my mother that Minnie always had such beautiful clothes. “It wasn’t always the case,” she said. “When she was your age she had two dresses to her name. I would wash one out at night so she always had one clean to wear to school.”

I learned from watching my sister what it meant to care for people, how to make them feel special and noticed. She did this so well. Maybe it started for her in high school when her boyfriend, an athletic young man and star of the football team came down with a virus. Before it was over, the entire team would be diagnosed with Polio. . . a terrible disease which left many of them with life-long paralysis and disabilities. Minnie married that high school football star and with the aid of crutches, braces, and then a cane, Charles was able to lead a normal life. She was a big part of that “normal life” part. She remained steadfast and strong throughout, as well as later in his life when he lost mobility of his legs and feet due to post polio syndrome. She was his rock for 58 years.

What I remember about Charles from my childhood is that he was witty and smart and his sarcasm was often lost on me. He tended to scare me a little and to hurt my feelings. But Minnie was always attuned to the moment and knew when maybe he had pushed it too far and she cleverly and carefully diverted the conversation to something safer. She was like that.

Minnie was one of the most generous people I have ever known. With her time, with her money, and with her attention. I don’t think many months went by that she didn’t drive the eight hours from her farm in Nebraska to our house in Colorado to visit my mother, my sister Lola, and me. She took us out to eat, a rare treat in those days, took my mother to run errands, and took me to buy a new dress for the first day of school or whatever the need was. One Christmas she bought me a HUGE pink stuffed poodle for my bed (something I would never have asked for because of the expense I imagined it would incur). She asked my mother for her engagement ring setting which had been long been missing its ruby stone and for years had sat naked in Mom’s jewelry box because she could not bear to part with it. Minnie retuned it to her with a new ruby on the next Mother’s Day. She took me shopping for a rocking chair for my high school graduation because she knew I would always need a rocking chair. And the list goes on.

Sometimes her generosity combined with the age gap could create an awkward moment. Paul remembers the time we made a trip to Nebraska for a visit after we were married. We had accompanied Minnie to the grocery store. As we were waking through the aisles, Minnie reached in her purse and pulled out a quarter which she gave to Paul, “Do you want a soda out of the machine?” “How old does she think I am? Ten?” Maybe twelve, I told him.

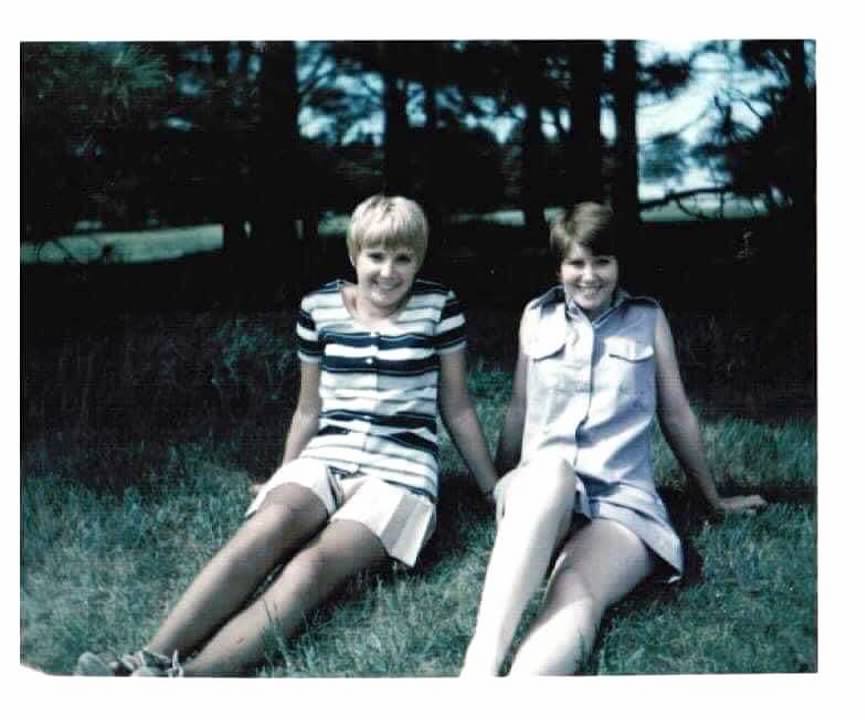

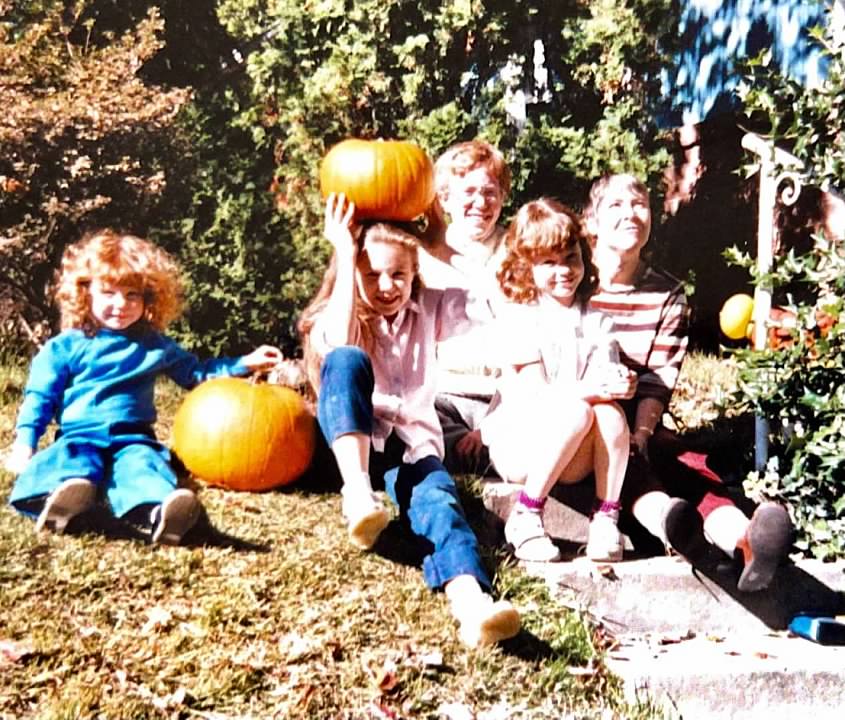

But perhaps the best gift she gave me was her daughter Shirley – one year younger than I. Our worlds were vastly different, yet we were fast friends. Shirley lived on a farm and loved all things outdoorsy, animals, and non-domestic. When Minnie and Charles moved from a house in town to the farm, Shirley was delighted – the farm came with a 30 year old horse named Sugar. Minnie became a 4-H leader and immediately signed her daughter up for” Let’s Cook,” “Let’s Sew” and “Let’s Groom Your Room” in an attempt to get her off the horse and out of the corrals. Shirley told me once, “I can still picture the old kitchen curtains she gave me to make my quick-trick skirt. I immediately saved my allowance money and paid a fellow member to do my sewing so I could pursue my trick riding.”

When Shirley came to visit me, her mother took us shopping and to Baskin Robbins. Without fail. We rode our bikes to the little store and got Cokes and Dreamcicles and Archie and Veronica comic books and came home to lie on my bed with the big pink poodle and read our newly purchased comic books. And my mother made her peach cobbler because it was her favorite and we pretended we were sisters instead of aunt and niece.

Shirley had a brother thirteen months younger than her. When he was in first grade his teacher told him he couldn’t come back to school until he had learned to write his first and last name. So Minnie sat him down at the kitchen table one Saturday afternoon and told him he wasn’t leaving that table until he could write Phil Smith on the paper in front of him. After a long and trying session he had mastered the assignment. But as he got up to leave she heard him say under his breath, “I’m just glad my name isn’t Marjorie Spikelmier”. I’m sure my sister was just as glad. This was the same Phil Smith who climbed the water tower of their small town the week before his high school graduation and spray painted his name on it in huge black letters. When called to the principal’s office and asked to explain himself, his defense was, “Do you think I would be dumb enough to paint my OWN name up there?” Apparently the principal thought exactly that because Phil was expelled and not allowed to graduate with his class. Instead he could attend graduation at a school in another small town a few miles away. “Okay,” his mother told him, “but YOU will be the one to call your grandmother who put in for vacation for this date a year ago and tell her you will be graduating next weekend instead.” It would seem Minnie was as afraid of my mother as I was.

Eventually Charles and Minnie left Nebraska for Texas. where the weather was warmer and it was easier on Charles. They owned and operated a feed lot there until they retired, moved to an apartment building for seniors and purchased a camper which they used to to visit the coastal areas of Padre Island, Corpus Christi, Brownsville, and many other places in Texas and Florida. Minnie was nothing if not flexible.

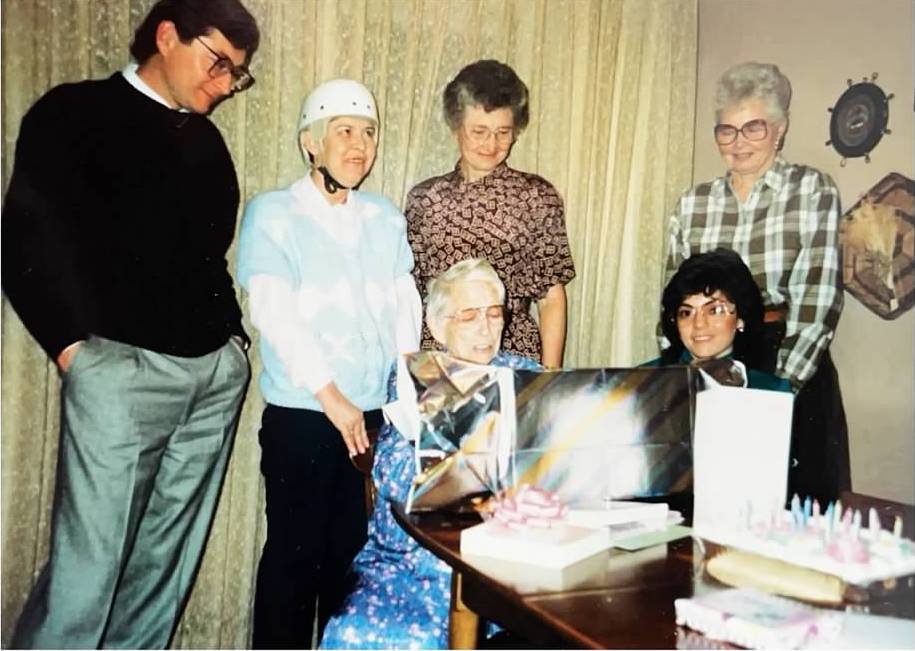

That apartment is where I went to visit her before she died. Our sister Lila and I flew to Texas to see her when Shirley had called to say, “If you’re coming, you might want to come now:” No sooner had we stepped through the door than she led us into her bedroom. “Come in here, girls. There’s something I need to show you.” She pulled out the ruby ring which my mother had left to her when she died. “Sherry, you should have this.” She put my mother’s gold wedding band in my sister’s hand. “And Lila, you take this.”

It was during that visit as I listened to Minnie and Lila and Charles reminisce about growing up together and the pranks my brothers played on them and the stories they told about a time and a place and people who were not a part of my story, that I learned more about her than I had ever known in all the years before.

I loved my sister. But what I discovered as i grew to adulthood is that I didn’t really know her. I had not grown up with her as had my brothers and sisters – had not shared their stories of poverty, of hardship, of war and life on a Nebraska farm. And she was not quick to share any of that. What I came to realize is that Minnie was a very private person. She simply did not talk much about her life or herself. When she was diagnosed with breast cancer, she did not share that information with her daughter, her sisters, or as far as I know anyone but her husband. No one knew when she had a mastectomy or reconstructive surgery. It was not until her doctor told her, “You really have to tell your daughter and sisters; they need that information”, that she shared it with us. When the cancer later returned as bone and then brain cancer, I learned it from our older sister. I called Minnie. “I’m so sorry,” I told her. There was a long pause. “Sherry, I’m so scared.” It was the most vulnerable I had ever known her to be and it broke my heart.

When Shirley was in fifth grade, her P.E. teacher once had this woman – the one with the perfect posture, the perfect way of walking through the world, the perfect sense of elegance – to come to class to teach the girls to walk with style and grace. “Like Minnie.” She was as close as our family got to royalty.

Thank you to my niece Shirley for sharing stories and details about her mother’s life which helped in the writing of this piece. It helped me to know my sister better and I hope to do justice to her story.